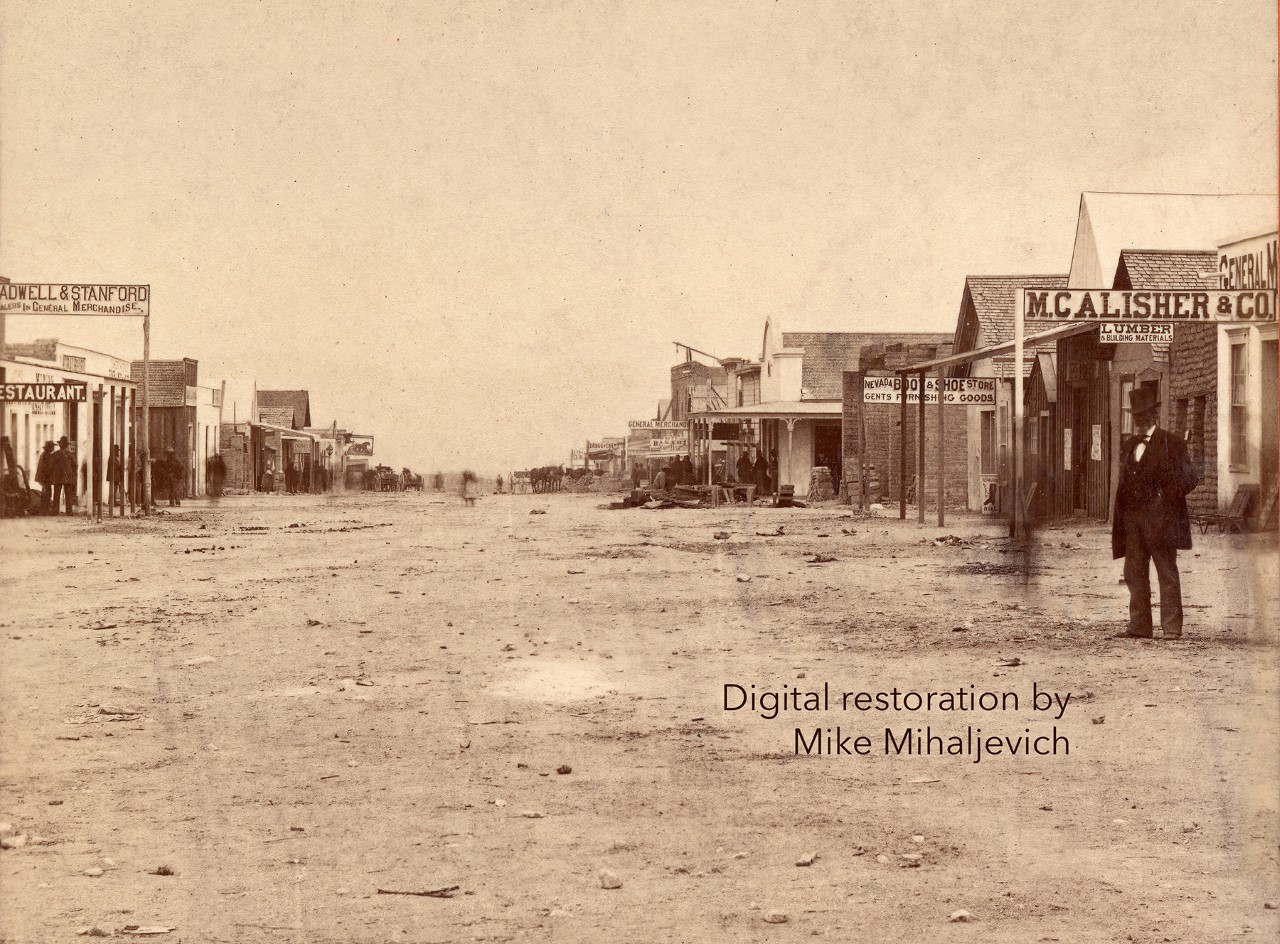

It was taken in late April, 1880, at a glorious time in Tombstone’s coming of age. The viewer is placed on Allen Street very near Sixth looking west towards Fifth with a direct view of the town’s growth spurt in full swing.

The man behind the camera was 50 year old Carleton Watkins. He wasn’t in Tombstone on a leisurely sight seeing adventure or a vacation or to seek mineral wealth. Arriving in San Francisco as a young man decades earlier he mastered the difficulties of chemical based photography and built a photo studio that earned him esteem among many social, political and business leaders. In 1875 he lost it all when the bank that financed his enterprise went under. To square his bills he sold 25 years worth of irreplaceable photographic work from all over the West to a local competitor and started over again. His trip to Tombstone was part of the long financial rebuilding process. Even as he boarded the train from San Francisco to Arizona in the spring of 1880, he didn’t have enough money to make the trip. En route he had to execute client work to cover travel expenses. Once he arrived in Arizona he waited on money sent to him from his wife who was scraping together a few sales at his gallery. He was one step below living paycheck-to-paycheck, because after all there was no paycheck guarantee.

Photographs he produced in and around Tombstone had to sell. The confidence he had in that might indicate the kinds of conversations about Tombstone that were going on in San Francisco at the time. But once he got there the elements battled him. Hot and dry conditions not only made him uncomfortable, it pitted him against blowing dust — the arch enemy of every period field photographer. His transportation around the area included a specialized wagon pulled by a team of mangy horses that disobeyed his commands. Arthritis in his neck made it hard to tote his mammoth plate camera which weighed over 50 pounds. An advanced tooth abscess made his first days in the area misery. With no money for accommodations he slept wherever he could, one night finding respite in a pile of hay and the next night a place “not half so good” as he wrote his wife.

Carleton battled it all as he set up his stereo camera on Allen Street amid the bustle of Tombstone’s boom. A few onlookers stopped and observed him at work. One man finely dressed in attire fitting of an established businessman stayed in place as Carleton executed the shot. Two impatient men on either side of him walked away halfway through the exposure (rendering as ghostly streaks in the final image).

The street before him was littered with rocks and debris, fitting for how rough hewn Tombstone still was. On either side were buildings — some still of temporary canvas, but many of adobe which signified the town was trending towards permanence. Down the right side of the street the second story of the Cosmopolitan was being added — a Tombstone first. A group of men clamored under the awning and in the doorway of the Golden Eagle Brewery (present day Crystal Palace) perhaps debating the hot topic of property rights that gripped early Tombstone.

Just before the Golden Eagle stands the unfinished walls of the Oriental saloon, with piles of unattended adobe bricks waiting to be installed. Its construction was finished shortly after Carleton left. Directly next door, Nellie Cashman’s Nevada boot and shoe store was doing great business with the miners. On the dirt sidewalk, Nellie placed a sign out front advertising “repairing neatly done” for budget conscious or down on their luck miners not ready for a new pair. Down the street is a cluster of wagons, more adobe walls under construction, dozens of men rumbling about, and many businesses serving an eager and buzzing population. The constant murmur of conversation mixed with horse hooves, hammers swinging, and an occasional outburst filled Carleton’s ears. It’s not just a street scene, it is a photograph of boom town madness!

In all, Carleton took 42 photographs in and around Tombstone. Many of them included mines and the industrial infrastructure that was of interest to potential photographic customers back in San Francisco. He also keyed in on permanent buildings and accommodations for lodging and stage travel — elements that communicated the degree of wealth being realized. To those with experience, these things signified the mines were legitimate. Six of those 42 photographs gift us a clear view of Tombstone’s Allen street during its most storied period. None exemplify it quite as well as this commonly published street scene. He did it all with the pressure of an empty wallet and conditions that tested his patience, his body, and his considerable abilities. So next time you see this photograph published (and I promise you, you will), think about what you’re really looking at. We are seeing Tombstone on the rise and a moment in the very difficult journey of world-class photographer Carleton Watkins. If not for his perseverance over innumerable difficulties and the mastery of his craft, we would never have seen it.

Written by Mike Mihaljevich