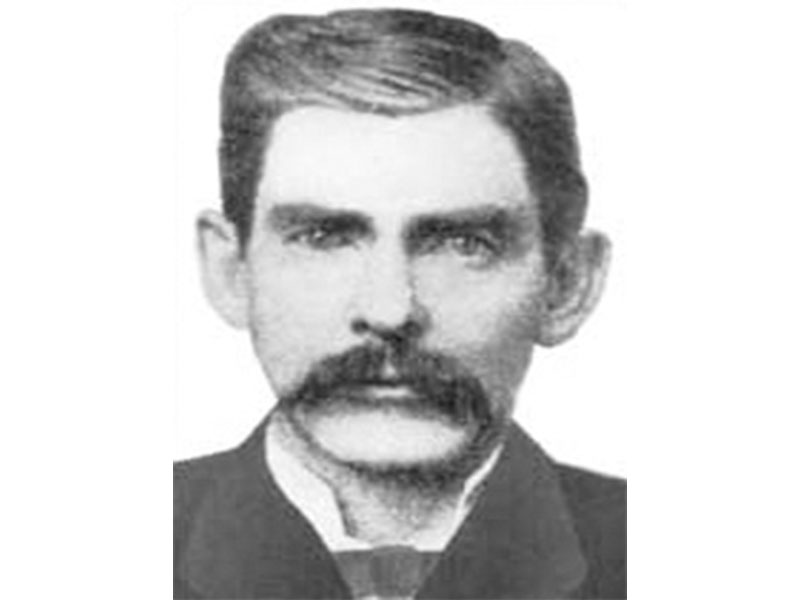

J. A. Holliday, or “Doc” Holliday as he was better known, came to Glenwood Springs from Leadville last May, and by his quiet and gentlemanly demeanor during his short stay and the fortitude and patience he displayed in his last two months of life, made many friends. Although a young man he had been in the west for twenty five years, and from a life of exposure and hardship had contracted consumption, from which he had been a constant sufferer for many years. Since he took up his residence at the Springs, the evil effects of the sulfur vapors arising from the hot springs on his weak lungs could be readily detected, and for the last few months it was seen that a dissolution was only the question of a little time, hence his death was not entirely unexpected. From the effects of the disease, from which he had suffered probably half his life, Holliday, at the time of his death looked like a man well advanced in years, for his hair was silvered and his form emaciated and bent, but he was only thirty-six years of age.

Holliday was born in Georgia, where relatives of his still reside. Twenty-five years ago, when but eleven years of age, he started for the west, and since that time he has probably been in every state and territory west of the Mississippi river. He served as sheriff in one of the counties in Arizona during the troublous times in that section, and served in other official capacities in different parts of the west. Of him it can be said that he represented law and order at all times and places. Either from a roving nature or while seeking a climate congenial to his disease, “Doc” kept moving about from place to place and finally in the early days of Leadville came to Colorado. After remaining there for several years he came to this section last spring. For the last two months his death was expected at any time; during the past fifty-seven days he had only been out of bed twice; the past two weeks he was delirious, and for twenty-four hours preceding his death he did not speak.

He was baptized in the Catholic church, but Father Ed. Downey being absent, Rev. W. S. Rudolph delivered the funeral address, and the remains were consigned to their final resting place in Linwood Cemetery at 4 o’clock on the afternoon of November 8th, in the presence of many friends. That “Doc” Holliday had his faults none will attempt to deny; but who among us has not, and who shall be the judge of these things?

He had only one correspondent among his relatives—a cousin, a Sister of Charity, in Atlanta, Georgia. She will be notified of his death, and will in turn advise any other relatives he may have living. Should there be an aged father or mother they will be pleased to learn that kind and sympathetic hands were about their son in his last hours, and that his remains were accorded Christian burial.[i]

There were a few inaccuracies in the newspaper report of Doc Holliday’s death. His initials were not J. A., but J. H., though that could have been a typesetter’s error. He wasn’t eleven when he left Georgia and traveled west, but twenty-three years old, after graduating dental school and practicing dentistry for a year. He wasn’t baptized a Catholic, though he may have been planning to receive that rite. And he certainly did not represent law and order “at all times and places,” though he had mostly stood on the side of the law. But beyond those points, his obituary written by Glenwood Springs reporter James Riland was thorough, detailed, and surprisingly sympathetic to a man who’d only lived in the town for six months, two of them bedridden.

The Denver Republican, which had sometimes supported Doc and sometimes not, also wrote kind words in honor of his passing:

Doc Holladay is dead. Few men have been better known in a certain class of sporting people, and few men of his character had more friends or stronger champions. He represented a class of man who are fast disappearing in the New West. He had the reputation of being a bunco man, desperado and bad man generally, yet he was a very mild mannered man; was genial and companionable, and had many excellent qualities. In Arizona he was associated with the Wyatt Earp gang. These men were officers of the law and were opposed to the “rustlers” or cattle thieves. Holladay killed several men during his life in Arizona and his body was full of wounds received in bloody encounters. His history was an interesting one. He was sometimes in the right, but quite often in the wrong, probably, in his various escapades.

The Doctor had only one deadly encounter in Colorado. This was in Leadville. He was well known in Denver and had lived here a good deal in the past few years. He had strong friends in some old-time detective officers and in certain representatives of the sporting element. He was a rather good looking man and his coolness and courage, his affable ways and fund of interesting experiences, won him many admirers. He was a strong friend a cool and determined enemy and a man of quite strong character. He has been well known to all the States and Territories west of Kentucky, which was his old home. His death took place at Glenwood Springs Tuesday morning.[ii]

The Denver paper, too, got some points wrong—Doc wasn’t around to correct his early history, after all, nor did he have family close by to state the facts—but anyone who’d heard him speak knew that he came from somewhere in the South. What both obituaries agreed on was that Doc Holliday had made many friends in Colorado—among them, Glenwood Springs policeman Perry Malaby, who claimed that he “passed the hat around town to raise money to defray Doc’s funeral expenses.”[iii]

The money collected for Doc’s final expenses went to Jacob Schwarz, who had an undertaker and embalmer shop in the back of his furniture and home decorating store on Grand Avenue, across Eighth Street from the Hotel Glenwood.[iv] Schwarz may have paid a house call to the hotel to prepare Doc’s body for burial, bringing along a satchel fitted out with jars filled with milky fluid, a small knife, a lancet and a syringe with various sized nozzles, or he may have had Doc’s body carried to his shop to do the embalming. As another undertaker of the time explained the process: “The art of embalming as practiced today is simply to preserve the body in a natural condition for a limited time.”[v] But as Doc’s time until burial was to be very limited—just a few hours—there may have been nothing more done than washing and dressing his corpse before placing it in a casket for a short trip to the cemetery.

The cemetery property had been donated by the undertaker himself earlier that year, to replace the original and inadequate cemetery in the center of town. The new site, on a high bluff with a panoramic view of the Valley of the Grand and a tortuous trail leading up from the edge of town, was originally called Jasper Mountain in honor of Glenwood Springs pioneer Jasper Ward, who’d been killed in a skirmish with Ute Indians that summer and buried on the bluff. But by the time Doc’s casket was hauled up the trail by wagon, with a line of friends following along as processional, the burial ground had been officially named Linwood Cemetery.

Although Doc had many friends in attendance at his graveside service, the funeral address delivered by the local Presbyterian minister would have been less than comforting. The Presbyterians’ belief that some men were destined for heaven and some for hell, with their earthly works showing which way they were headed after death, was one of the reasons his mother had broken with that denomination and left her written testimony for her son. But the Reverend Rudolf’s sermon celebrating the resurrection of the just was likely also a reminder of the wages of sin, of ashes to ashes and dust to dust, and a warning to other sporting men. And then Doc Holliday’s remains were consigned to the care of God.

But that wasn’t the end of his story, nor of his travels on the railroad. For according to a tradition out of his old hometown, Doc took one more ride on the rails—as freight loaded on a train back to Georgia. As the story goes, when Henry Holliday learned of his son’s death in the cold mountains of Colorado, he had the grave opened and the casket brought up and sent back home for a second burial in a private and unmarked grave in Griffin.[vi]

That story began to be retold in the early 20th century, when a group of ladies working to beautify Griffin’s Oak Hill Cemetery were given a tour of some of the prominent burials by the cemetery’s sexton—including the grave of the famous Doc Holliday. The old gentleman told the ladies that caring for Doc’s grave had been the duty of the sextons for years, along with the care of other special burial sites. So, based on the tradition, the City of Griffin placed a small marker at the site, stating simply, Some historians believe that Doc Holliday is buried here.

In 2014, a series of brass plaques was planned to mark sites relating to Doc’s childhood in Griffin: the Tinsley Street home where he was born in 1851, the Presbyterian Church where he was christened in 1852, the Solomon Street building that was his inheritance from his mother and where he practiced dentistry before going west, and the possible plot in Oak Hill Cemetery. But when the local paper published a story about the placement of the plaques, a Griffin lawyer contacted the City Commissioner in charge of the project.

“I hear you’re going to put a Doc Holliday marker in my family’s plot,” the man said.

The Commissioner was surprised by the call and disappointed to hear that Doc Holliday wasn’t back in Griffin, after all.

“Oh, he’s there, all right,” the lawyer said. “My great-grandfather was friends with Doc when they were young, so when his father needed a place to put him, he contacted the family and made the arrangements. That story has been in our family for a hundred years.”

It’s not proof, of course, but it’s the next best thing: a family story that’s been kept quiet to protect the privacy of a man whose life had been far too public. Now a beautiful brass plaque marks the spot where some say—and many believe—John Henry Holliday is finally home from his journeys and resting in peace.

Source: The World of Doc Holliday: History & Historic Images copyright 2019 Victoria Wilcox, TwoDot Books/Globe Pequot

[i] Glenwood Springs Ute Chief, November 12, 1887. No remaining copies of the paper exist, but the obituary is found in the scrapbook of reporter James L. Riland, in the collection of the Colorado Historical Society MSS #520, Scrapbook #3 p. 53

[ii] Denver Republican, November 10, 1887

[iii] Duffy, “Doc Buried Here?” It seems appropriate that when historian Nellie Duffy, who wrote about Doc Holliday’s burial, died on August 4, 1997, she became the last person to be buried in the old Linwood Cemetery where Doc was laid to rest.

[iv] Willa Kane, “Undertaking a New Life in Glenwood,” Post Independent/Citizen Telegram, November 9, 2014

[v] “The Art of Embalming,” Aspen Daily Times, July 20, 1887

[vi] Della A. Jones, “Where’s Doc?”, tombstonetimes.com. The story of the Griffin grave was also told to the Author by the grandson of Laura Mae Clark and by Oak Hill superintendent Osgood Miller, who both heard it from the former sexton of the cemetery. The story of the lawyer’s family plot was told to the Author by Griffin City Commissioner Dick Morrow.